170th Anniversary of Posada

I stumbled upon an exhibit celebrating 170 years of Posada artwork at Rockefeller Center the other day. It was a small display of his work but I enjoyed the time seeing the illustrations up close. It was late and no one was there so I got to enjoy it by myself.

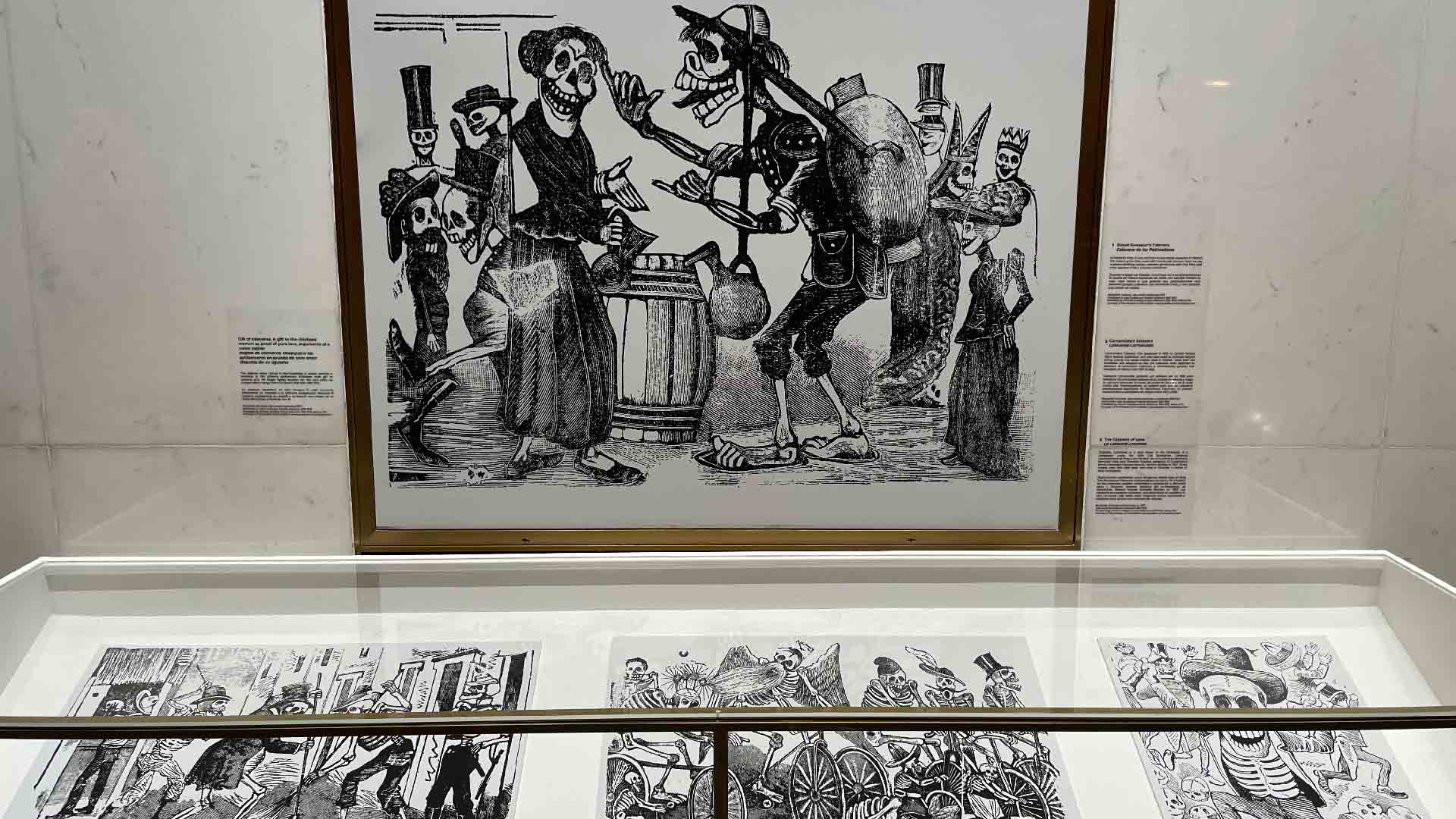

A display of calaveras for Dia de Los Muertos outside the Rockefeller Building. Calaveras means skeletons in Spanish.

About José Guadalupe Posada

José Guadalupe Posada was born in Aguascalientes, Mexico, on February 2, 1852, and died on January 20, 1913. During the first stage of his life, Posada acquired elementary experience in design in the pottery workshop of one of his uncles. He later received formal education at the Municipal Drawing Academy. After completing his studies at age fifteen, Posada registered as a pointer, and one year later he learned lithography (the study of printmaking) while working as an illustrator in the workshop of José Trinidad Pedroza.

In 1872 Posada moved to Leon where he worked with various techniques from lithography to engraving. The subject matter of his work was varied, including political cartoons, advertising, religious images, and newspaper illustrations.

In 1887 after a flood destroyed his workshop, Posada moved to Mexico City where he opened his first studio on Calle Cerrada de Santa Teresa. During this time, Posada is known to have created images for more than fifty-two Mexico City magazines. His collaboration with the publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo between 1888 and 1913 stands out and gave rise to innumerable images.

Posada died as an unknown artist at the age of 61 and was buried in an unmarked grave. In the 1920s, the French artist Jean Charlot celebrated Posada’s work internationally, describing him as the “engraver of the Mexican people.” His art, Charlot thought, was deeply rooted in Mexican history and had an important influence on the modern art movement in Mexico.

This was demonstrated when two of the most recognized Mexican muralists, Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and José Clemente Orozco (1883 – 1949) acknowledged Posada as a source of inspiration. Posada’s artistic influence is also reflected in the works of Leopoldo Mendez, Pablo O’Higgins, and Luis Arenal, all of whom are renowned founders of the famous graphic artists’ collective Taller de Gráfica Popular.

A display showcasing some of Guadalupe’s illustrations.

The Mexican Day of the Dead

Each year, during the holiday known as Dia de Los Muertos (Day of the Dead), it is believed that the souls of the departed return to earth, where they are welcomed as honored guests by family and friends. The origin of this tradition is found in the commemoration of the Day of the Dead that the indigenous people carried out since pre-Hispanic times and its harmonization with the celebration of Catholic religious rituals brought by the Spanish.

Upon dying it was believed that the souls traveled to Chiconauhmictlán, the Land of the Dead. Only after getting through the nine challenging levels of the underworld, could the person’s soul finally reach Mictlan, the final resting place. The Day of the Dead in the indigenous vision implies the transitory return of the souls of the deceased, who come back home to the world of the living to visit their relatives and be nourished by the essence of the food and beverages that are offered to them in the ofrendas placed in their honor.

According to tradition the border between the spirit world and the real-world dissolves at midnight, and the spirits of children and adults can rejoin their families from November 1st to November 2nd.

Posada’s Calaveras

The use of skulls, skeletons, or calaveras as symbolic imagery is among the oldest traditional elements included in celebrations of Dia de Los Muertos. Calaveras has become so commonly used that they are nearly synonymous with the holiday. Sugar skulls, full-sized paper mache skeletons, calvera ceramics, masks, and other representations of death have found their way into the ofrendas in Mexico and increasingly into millions of homes around the world.

The association of calaveras with Dia de Los Muertos may have begun in the ancient traditions of the Mexican people. However, its worldwide modern popularization is due mainly to the work of two Mexican artists: José Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Manilla (1820 -1895). While working during the late 19th and early 20th century for the Mexico City publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, Posada and Manilla created thousands of images to illustrate the editorial’s publications.

“Penny press” broadsides were commonly used to communicate news and articles of the day. These broadsides were very popular around the dates of Dia de Los Muertos as they would feature calavera images, often satirizing current events or popular characters, or depicting calaveras in life mocking activities to remind readers of their future shared destiny: death.

The art showcased provides a sampling of the many calavera images crafted by Posada. It is a memorial to him for his contribution and influence on past, present, and future generations of artists. It is also meant to serve as a portal through which the dead may be brought back, allowing us to reflect on the nature of life and death.

La Calavera Oaxaqueña

La Calavera de Don Quijote

Calavera Carrancista

Calavera de los patinadores

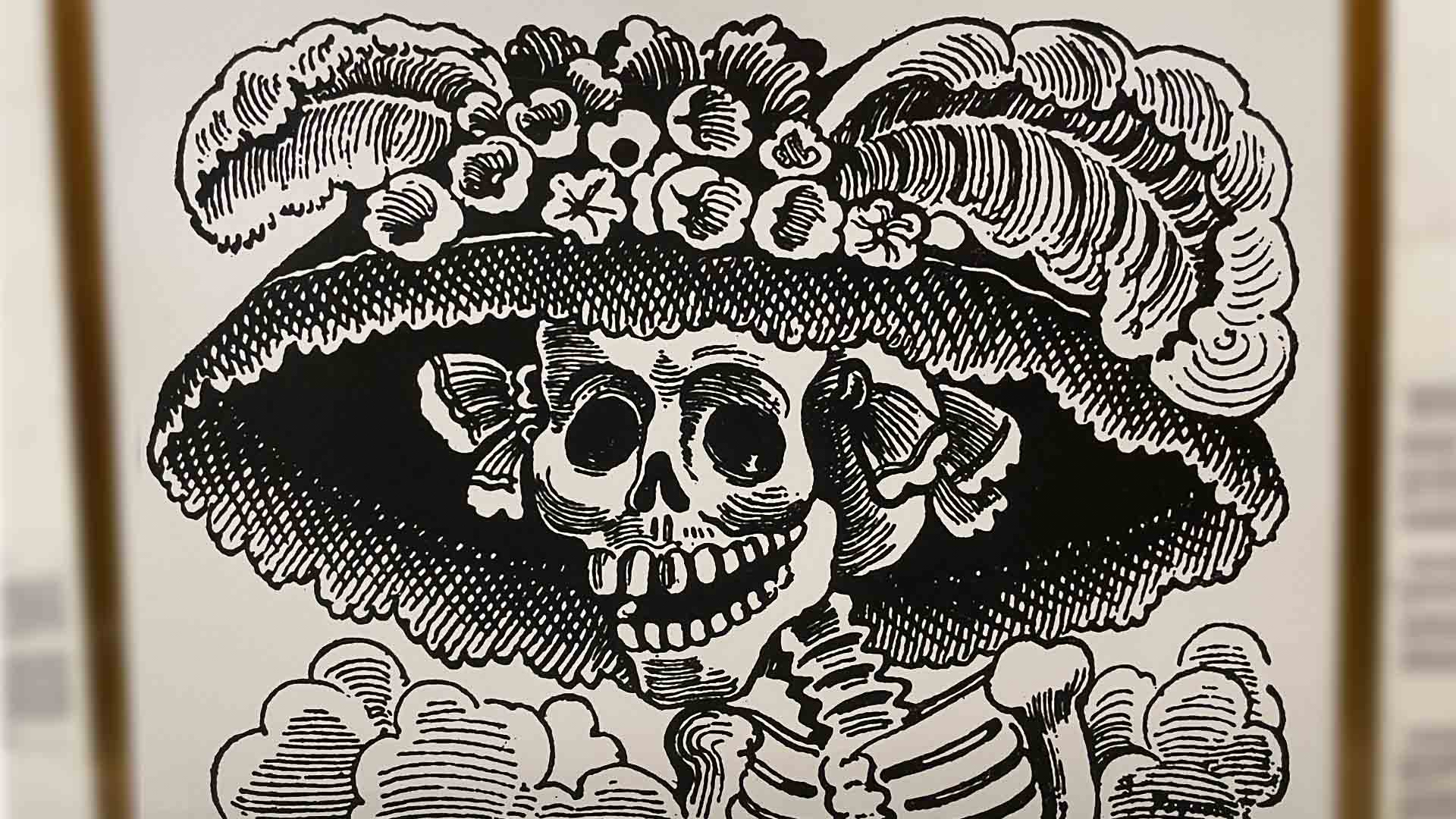

El Panteón de las Pelonas

This image is perhaps Posada’s most popular illustration. Originally appeared in an undated newspaper broadside (believed to be 1912), roughly four months before Posada’s death in 1913. In 1924 the image was used again after a controversy erupted in Mexico City over short hairstyles for women, sparking protests by men who felt threatened by this new look.

In this broadside published by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo’s son, la Catrina is bald. Addressing the women, the speaker laments: “Your determination to enjoy yourselves and to cut your hair, made you should pass from earth to heaven. You have lost our charm and you have lost our warmth, and you have therefore lost the hoys of our love.”

Closing Thoughts

It was a nice experience to be walking around New York City and unexpectedly find an art exhibit. Of course, I had to go investigate and learn! What did you think about the Posada gallery at Rockefeller Center?

More Treasures to Discover

Learn about the latest news in El Salvador through Walkway, a free extension developed for Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge. Enjoy photographs of El Salvador, taken by national photographers, every time you open a new tab. The Walkway extension is perfect for locals, tourists, and people who love to travel. It’s also a portal to continue enjoying the content on Life’s Hectic.